The Fern Life Cycle

Overview

Most sources that describe the Fern Life Cycle speak the foreign language of botanists and environmental scientists, delving into more detail than anyone - except the plant's mother and high school science students - needs to know. Here's the basics for the everyday Indoor Gardener.

If you are interested in more details, click here to visit the Fern Life Cycle - In Depth page.

Since it is a cycle, we can start discussing it anywhere along the path - sort of the houseplant version of which came first, the chicken or the egg.

Let's assume for the moment it's the egg. Or the egg-like spore.

Spores are the defining attribute of ferns, distinguishing them high up the taxonomic chain from other plants that propagate by seed.

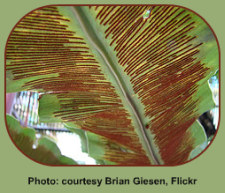

These single cells grow on the underside of fertile fronds (not all fronds are reproducers), and can appear one at a time, in rows, or in clusters.

The Button Fern, for instance, displays its spores in a dainty little circle around the edges of the small, round leaves while the Rabbit Foot Fern has earned its Wart Fern nickname due to the spores that push up from underneath, creating wart-like bumps on the top side of the fronds.

When mature, the spores burst out of the protective covering creating a fine, colored dust. Depending on the species of fern, common colors range across most of the spectrum: brown, red, yellow, green, black.

The spore dust travels predominantly through rain and moisture, but is helped along by wind, birds, or other forest animals who carry it until it settles onto the lush, nutrient-rich ground of the fern's natural habitat.

Each spore carries one copy of each chromosome. As it settles to the forest floor it develops into a gametophyte, a small, autonomous plant that hooks onto the forest floor with rhizoids and later, roots. It produces both male sperm and a female egg. These join together in a zygote, which is an "infant" fern.

As the zygote develops it grows into an embryo and becomes independent of the gametophyte. Eventually, the new plant grows fronds from the rhizomes and uncurls in the familiar fiddlehead pattern until it spreads its wings into its full leaf-like state. Some but not all the fronds mature into sporophylls, which produce their own spores - and the fern life cycle continues.

Click here to read our Disclosure Statement.

Click the image to ORDER and get more information

Although I don't own this one, I do have one of the Success With... series for indoor plants -- it's basic, to the point, and quite helpful. A plus for your indoor gardener library, Indoor Ferns by Susan Amberger-Ochsenbauer, also makes a good gift for a plant-growing friend.

Other Propagation Routes

Some ferns have other or additional ways to reproduce.

Apogamy is the process whereby a sporophyte is able to grow from the gametophyte bypassing the fertilization process. Ferns might use this process if they naturally live in a dry environment.

Rhizome and tuberous ferns can spread and grow new plants, which is a process used by brackens. The Indoor Gardener can emulate this process by root, rhizome, or tuber division.

Yet other ferns, such as the Mother Spleenwort Fern, grow plantlets right at the edges of their fronds. The Indoor Gardener can then root the baby plants in another pot. In the wild, the adult frond arches over to root the plantlets in the soil.

An Indoor Gardener, with patience, diligence, and time,

can learn to propagate ferns from spores.

If you're like to read a more in-depth

description of the Fern Life Cycle

,

click on this link.

Return from the Overview to

Indoor Gardener Home Page